Boredom is Killing Creativity

By Rehan Khan

25-03-2024

The digital milieu in which we exist has transformed our behaviour into scavengers, rummagers, hunters - we incessantly seek, crave, search for new information from our digital devices and platforms. And when we can’t find the newest and shiniest, boredom sets in.

Boredom has been defined as “the aversive experience of wanting, but being unable, to engage in satisfying activity” by John Eastwood at York University. More specifically Eastwood and his colleagues say that boredom sets in when we cannot engage with internal thoughts and feelings, or external stimuli that is satisfying, and we assign this to the state we are in, or the environment within which we exist. In other words, the person wants to be stimulated but is unable to do so.

A Nielsen study examining the motivations for using smartphone apps found the top three reasons were: while alone (70 percent), when bored or killing time (68 percent), or while waiting for something or someone (61 percent). People preferred to be stimulated as opposed to sit alone, reflect, ponder and go deep within themselves. A UK study also found that 62 percent aged between 18-30 preferred to use their device rather than just sit and think.

Adam Gazzaley and Larry Rosen authors of The Distracted Mind, hypothesize that boredom has increased in recent times due to the influence of pervasive short timescale reward cycles in modern media. Gazzaley and Rosen say that from decades of research on learning and behaviour, we know that the shorter the time between reinforcements (rewards), the stronger the drive to complete that behavior and gain the reward.

In video games like Temple Run, which has been downloaded more than one billion times, players collect coins in each moment of the game – this frequent collection of rewards has according to Gazzaley and Rosen altered our boredom profile, so that when we engage in less stimulating information such as reading a book it has a much longer time-scale reward structure – as you need to get to the end of each chapter and of course complete the book.

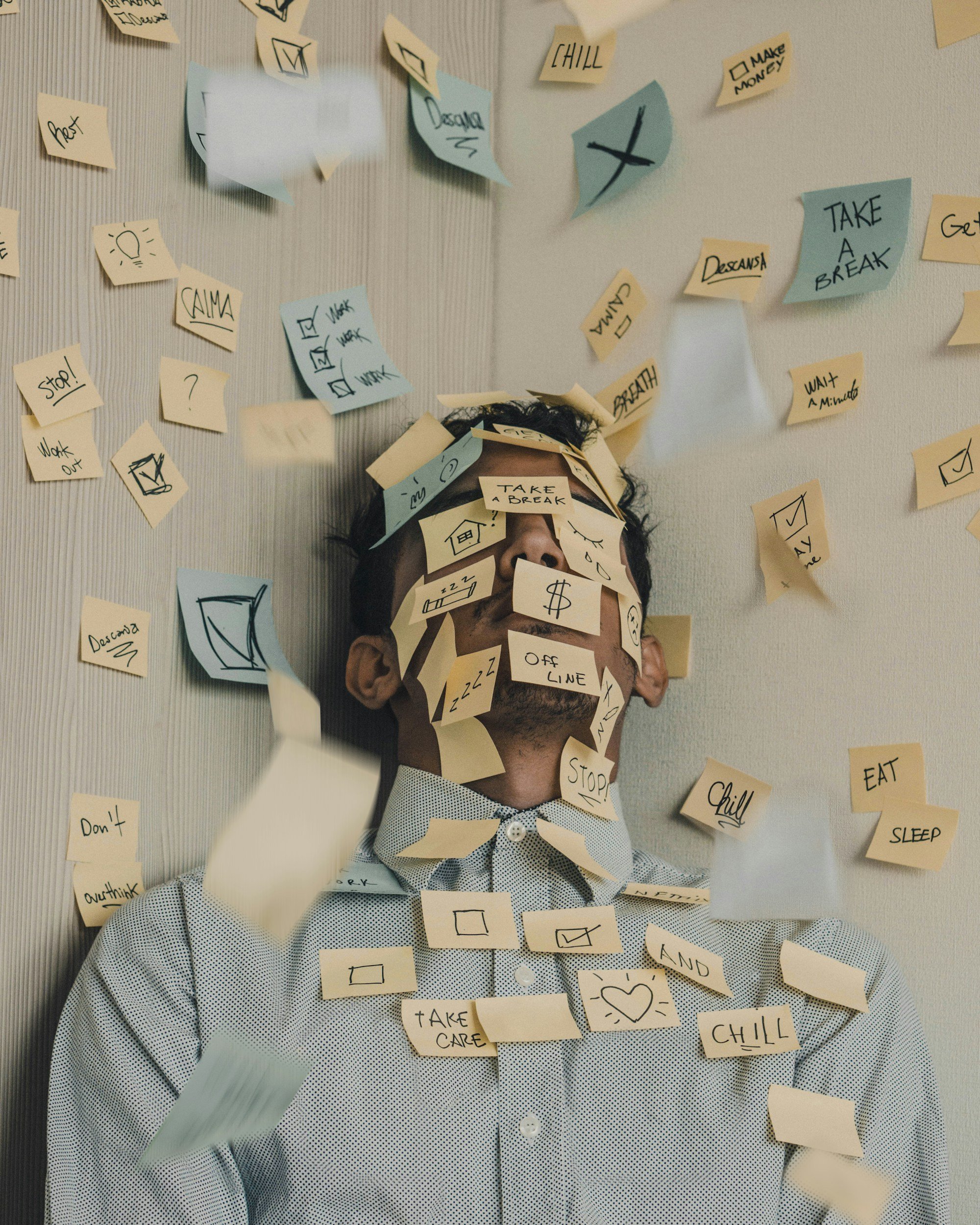

In corporate settings, this same immediacy around rewards can be witnessed as we incessantly multi-task, jumping between messaging platforms and tasks. If we don’t receive an immediate reward, then boredom takes hold and we switch tasks, which has its cognitive costs, and so the cycle continues spiraling downward.

In one study at Kent State University, researchers found that college students who were “heavy smartphone users” (ten hours per day) frequently referred to boredom as the motivator for using their smartphones. In addition, they were more likely to be prone to leisure boredom than students who were classified as “low smartphone users” (three hours per day). Elsewehre, a study from the University of Waterloo reported that university students susceptible to boredom overestimated the passage of time – to them a minute felt like an hour.

One educator, Teresa Belton, from the University of East Anglia, added: “Whenever children are bored, they’re likely to turn on one of those electronic things and be bombarded with stimuli from the external world rather than having to rely on internal resources or devise their own activities.”

Using smartphone as a crutch to overcome boredom is not unfortunately limited to children and the young, rather this is a pervasive problem which we are all prone to in our working and personal lives. We would rather be showered with an avalanche of social media notifications, silly animal videos and other non-sensical stimuli than take a moment to journey inward and do the hard work of making ourselves better.

When we get busy fixing our own shortcomings, which we all have, there is no time for boredom because we realise how much work there is to do. In addition, thinking deeply, reflecting and pondering, letting our minds rest, this is when we have the best ideas, as we enable our brains to join the dots that we would have otherwise missed as we were too busy thinking we were bored and had nothing to do.